Hidden Dangers: Silica dust levels in coal mines were concealed for years while black lung cases surged

As of 2018, one in five central Appalachian miners who had worked at least 25 years were found with the disease, according to a study.

As the giant machines churned through the deep rock, coal miner Kevin Weikle found a way to conceal the toxic dust that bombarded his lungs for hours at a time.

He stuffed the portable air monitor that he was required to wear deep inside his overalls each shift.

Though he and his fellow workers managed to hide the dangerous levels of dust from federal inspectors for years, he couldn't protect himself.

Kevin Weikle poses on his driveway on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia. Kevin, now 35, went on disability a year ago after being diagnosed with complicated black lung. He started working in a coal mine six months after graduating high school at 18. Mr. Weikle says he now wants to speak on behalf of coal miners -- especially the younger workers --who are exposed to silica dust, which can leads to the most egregious form of black lung. He said he hopes a new federal rule, which cuts in half the amount of silica that can be exposed to miners, helps to stem the rise in the disease.

Kevin Weikle looks out his window as he drives to get his daughter breakfast by his home on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

The 35-year-old father of two young children is now ravaged by the very toxins that he had been concealing all those years in the mines of West Virginia.

He is among the new generation of underground workers who have been inflicted with a virulent form of black lung, an irreversible disease caused by breathing in the silica dust that kicks up inside some of the oldest manmade caverns in the country.

Since his diagnosis a year ago, his breathing has worsened. He can no longer sleep lying flat on his back or he will wake up choking. He struggles to walk short distances and carry out some of the most basic tasks in life.

On some days, "it's like a ticking time bomb," he said.

One of Elk Run’s Coal Company mines off of Coal River Rd. on Sunday, July 14, 2024, in Whitesville, West Virginia.

Kevin Weikle, left, sharpens a chainsaw with his dad, Brady, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia

For decades, miners have come down with the disease after inhaling coal dust. But as the layers of coal became thinner, young workers were forced to dig deeper into quartz rock, which generates the silica dust — a carcinogen that has led to the most dangerous spike of black lung in more than a generation.

As of 2018, one in five central Appalachian miners who had worked at least 25 years were found with the disease, according to a study by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The region’s miners are eight times more likely to die from the illness than anyone else in the country, the agency says.

Dixie Weikle, 5, rests on her father, Kevin’s, as the two sit on Kevin’s porch on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

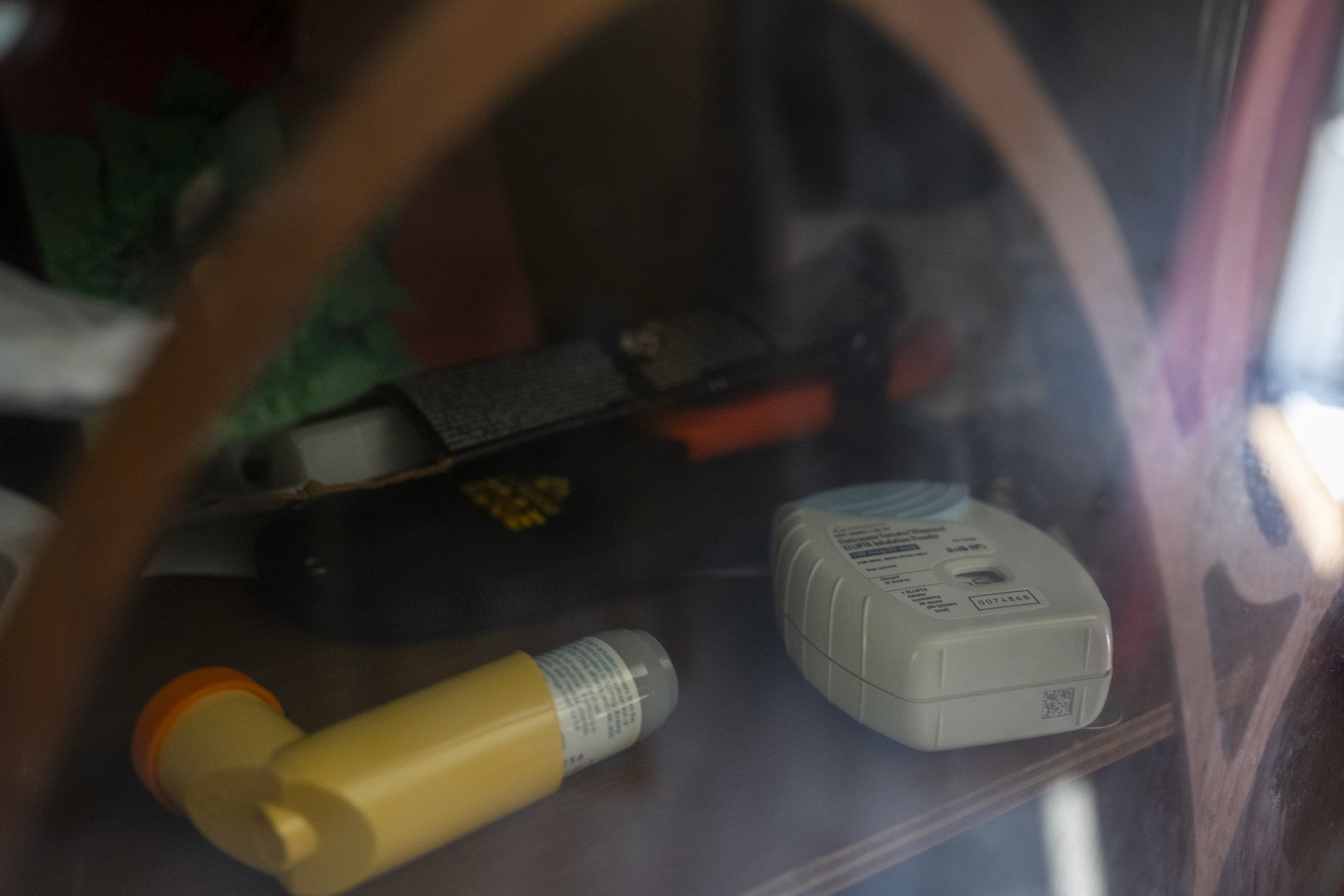

Kevin Weikle’s inhalers are scattered around his home on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

Earlier this year, a long-awaited protection was put in place by federal regulators to cut in half the amount of silica dust that miners can be exposed to during a shift — a critical reform that safety experts say could save hundreds of lives.

But veterans like Mr. Weikle say the biggest challenge over the next year will be enforcing those protections.

Because mine operators are largely responsible for tracking the dust levels to make sure the government's standards are met, much of the burden of upholding the rule will be placed on some of the very companies that spent years hiding the hazards, he said.

“It's insane to let these companies have that much authority," said Mr. Weikle, who entered the mines after graduating from high school in 2007.

Kevin Weikle shows his daughter Dixie his old lunch box from when he was a coal miner on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia. The lunch box is a repurposed bit box, and miners often use these boxes for their durability inside the mine. “I’ve lost a few lunches from being crushed,” Kevin shared with a laugh. He added, “You get used to the taste of coal; the dust is everywhere.”

Dixie Weikle, 5, and her father, Kevin, search for Dixie’s sheep on Kevin’s hobby farm by his home on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia. Kevin, now 35, went on disability a year ago after being diagnosed with complicated black lung. He started working in a coal mine six months after graduating high school at 18. The hobby farm and his black lung disability are Kevin’s primary sources of income, but “it’s not enough,” Mr. Weikle shared.

Kevin Weikle stares at his daughter and father as the two hang out in his living room on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

The rule, which kicked into effect in June, came after long and often contentious debates over the new protections expected to cost operators tens of millions collectively each year to put into place.

To meet the new limit, many mining companies will have to install engineering controls to suppress, divert or capture dust, and in some cases, improve ventilation systems or put up physical barriers between miners and dust.

Federal regulators estimate the larger mining sector could incur more than $57 million in costs each year, while industry representatives say some of the sampling alone could cost more than $100,000 per mine.

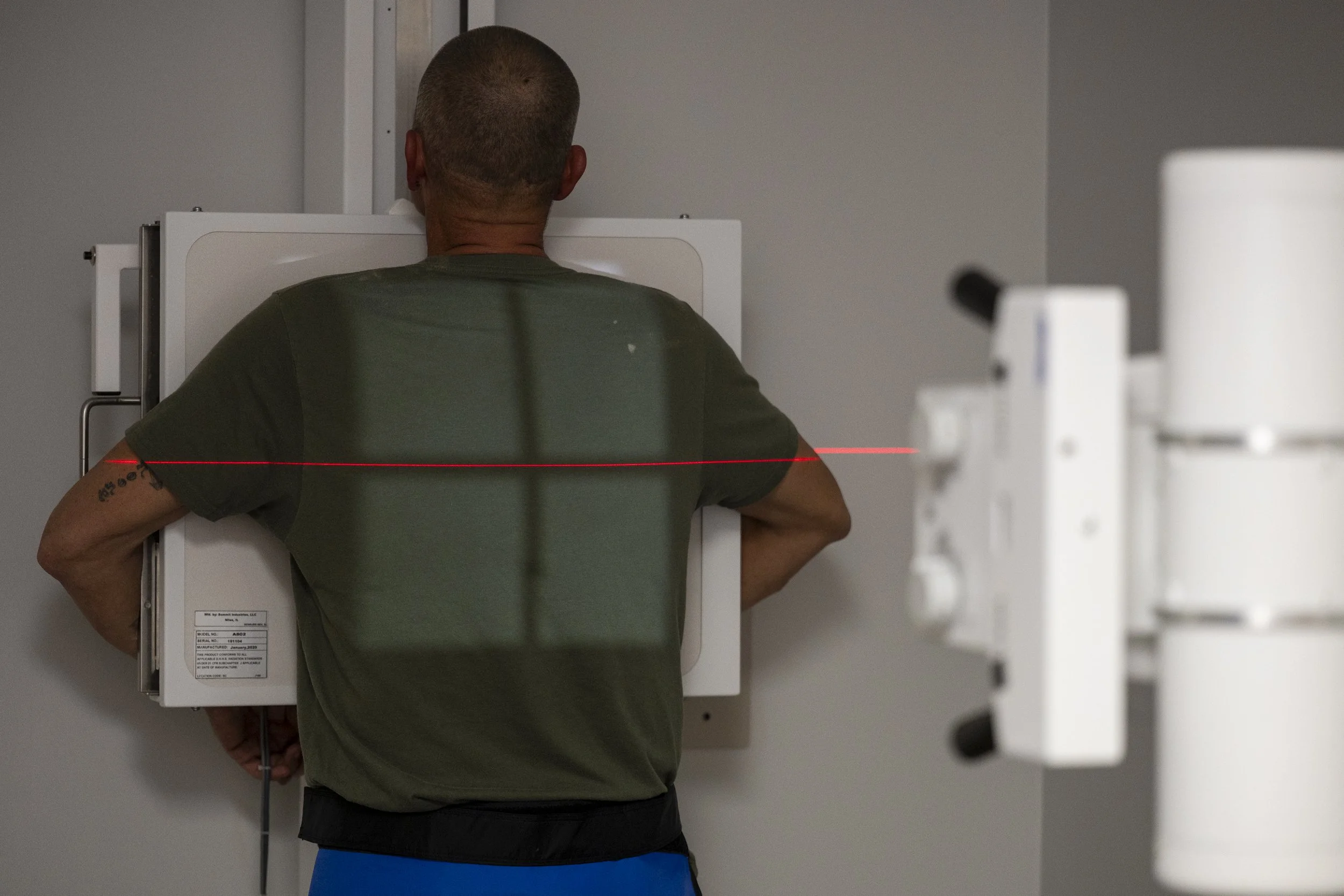

An anonymous X-ray shows a coal miner’s black lung last week at the New River Black Lung Clinic in Oak Hill, W.Va.

By Kevin Weikle’s front door hangs a photo of him mining at the age of 19 on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

While the measure sets up potential clashes between powerful forces in mining — including large operators and labor leaders — the goal was to stem one of the most insidious diseases to ever impact underground workers.

"It's heartbreaking. Many of them will die from this," said Lisa Emery, a respiratory therapist who directs a black lung clinic in Oak Hill, one of the hardest hit areas of West Virginia. "They don't get the respect that they deserve."

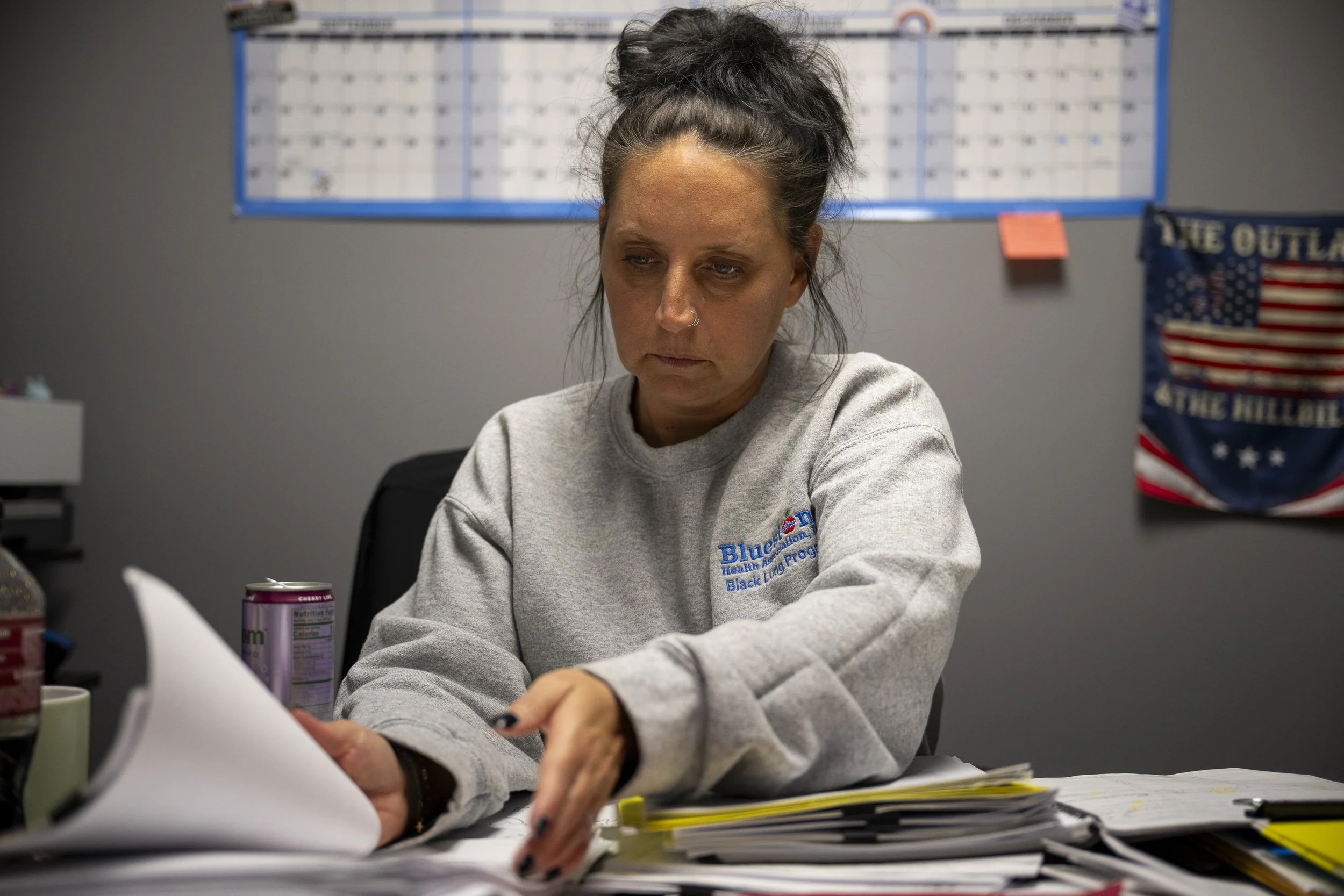

Lisa Emery, Breathing Center director at the New River Health Association's Black Lung Clinic and respiratory therapist, sits behind her desk at the New River Health clinic on Tuesday, July 16, 2024, in Oak Hill, West Virginia

By Kevin Weikle’s front door hangs his old “black hat” helmet on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.

Day after day, Ms. Emery tests the lung function of coal miners to see how the exposure impacts the way they are breathing.

The number of miners diagnosed with progressive massive fibrosis — the severe form of black lung caused by silica dust — has increased at rates she has never seen.

"I had five [cases] in February. I easily get three a month. These are younger miners in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. You cry together. You get to know them and their families. This is not your grandfather's disease."

Though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pushed for the new standard on silica starting in 1974 — halving the limits to 50 micrograms per cubic meter — the government didn't impose the reform for coal mines, leaving some workers exposed to levels of toxins far beyond the levels of safety.

Over the years, the combination of the coal and silica dust created conditions, including thick walls of dust, that left thousands of miners vulnerable.

Danny Johnson, 70, a retired West Virginia miner from Mercer County and plagued by advanced black lung, said he'd be so covered with dust after working a shift underground, "you could only see the whites of my eyes."

For Mr. Johnson and others, tiny sharp particles tear into their lungs, creating scarring and a thickening of the inner walls of the tissue that make it much more difficult for the patients to breathe.

As cases of the advanced disease began to increase — the first wave reported in 2005 — safety advocates pressed the Mine Safety and Health Administration to look for ways to crack down and impose new restrictions.

Even when the new rule was unveiled last year — a half century after it was first proposed — MSHA still left it up to the operators to track the dust in their mines.

As it now exists, the operators will collect frequent samples in each mine and must report all cases of overexposure to federal regulators, while the government will monitor underground mines four times a year and collect data.

The new rule comes after years of fighting over what some leaders of the United Mine Workers of America call longstanding cheating in the industry to avoid violations — allegations that the industry has denied.

An analysis by the Post-Gazette and the Medill Investigative Lab found that at least 103 mines have been slapped with violations for tampering with samples taken from the mines to track dust levels since 2000.

That includes four mines in Pennsylvania, the fifth-largest state for coal production, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Of those, three were owned by Rosebud Mining Co., based in Kittanning.

“Anyone who wants to tamper with samples can simply put the sampling device in a lunch box, and that's the end of it,” said Richard Miller, a former U.S. House labor policy director.

The hotbed for tampering has been Kentucky — more than a third of all violations, according to the data. In the past two years, multiple mine operators there have even faced criminal charges for their roles in sampling fraud.

In 2022, a federal judge sentenced two Armstrong Coal Co. mine managers to six months probation after they repeatedly removed dust monitors off of miners.

And last year, a certified dust examiner at Black Diamond Coal Co. was sentenced to six months in prison, six months of home detention, and a year of supervised release for submitting false samples and “lying to MSHA special investigators,” prosecutors said.

In their own public letters, industry representatives such as the Pennsylvania Coal Alliance continued to reject allegations of widespread manipulation.

“Frankly, as an industry, [we] are weary of the constant accusations that are absent of evidence,” the state’s primary trade group said.

The number of mines that will be impacted by the new rule is formidable.

Consider: at least 439 across the country exceeded the limits in sample tests in the last five years and more than half of those mines surpassed even the more lenient former threshold, a Post-Gazette analysis found.

The changes would “impose a tremendous, unnecessary burden on mine operators and miners,” the Silica Safety Coalition, a group of mining companies, wrote in a letter to MSHA last year.

Some companies, which must fully comply with the rule by next June, said they will do what it takes to meet the new standards. One of the largest operators in the nation, Consol Energy, of Cecil,supports the new standard, according to a statement from its vice president of safety, Todd Moore.

"We will continue to rely on a comprehensive use of controls and procedures as well as the use of personal protective equipment to best protect our employees," he said.

Mr. Weikle spent nearly a decade in the deep seams that run through coal country in West Virginia, which includes some of the richest mines in the nation.

By Kevin Weikle’s front door hangs a photo of him mining at the age of 19 on Monday, July 15, 2024, in Peterstown, West Virginia.(Benjamin B. Braun/Post-Gazette)

Like so many, he began drilling for coal at 18, at first with Massey Energy and later, Alpha Natural Resources.

While working for both companies, he said he was often expected along with other workers to make sure federal inspectors only read the samples of those pumps placed away from the massive amounts of dust billowing up from the coal and sandstone.

"I would put [the portable dust pump] down into my bib," he said, adding, "or you place them where there is no dust."

Massey Energy was purchased by Alpha Natural Resources in 2011 after one of the nation’s worst mining disasters: The Upper Big Branch Mine explosion in West Virginia, where 29 workers were killed in a coal dust explosion.

Alpha Natural Resources was acquired by Contura Energy in 2018 and the company has since been renamed Alpha Metallurgical Resources, headquartered in Tennessee.

Mr. Weikle, who was diagnosed with black lung disease in July 2023, said that during a meeting earlier this year held by safety advocates and attorneys for miners, he told them that they needed to make sure the companies keep up their end.

He said he believes that if the measure had been in place during his years as a miner, he would not have been exposed to the same level of toxins. After years, "the silica dust cut my lungs all to pieces," he said.

He said he's forced to sleep in a reclined bed, otherwise he chokes on phlegm that drains from his respiratory system. He is unable to walk long distances or uphill without gasping for air.

"It just keeps getting worse and worse," he said.

He said if his lungs continue to deteriorate, he will be placed on the organ transplant list.

Much of his time is now spent with his two children, ages 5 and 12, and driving to the lung clinic in Oak Hill, W.Va., where he goes for check-ups. He said he became angry recently after learning that some members of the U.S. House tried to stop the government from imposing the protections by cutting off any funding for enforcement.

So far, the House Appropriations Committee has not adopted the amendment that was pushed by U.S. Rep. Scott Perry, R-York, but Mr. Weikle said he fears that the reform — the most sweeping in a generation — will continue to be challenged.

"All they have to do is to do what they're supposed to do," he said.

Mr. Weikle, who lives in Peterstown in southern West Virginia, said much of the burden of ensuring protections are in place will depend on how vigorously MSHA enforces the rule.

Last year, he was interviewed by Ted Koppel on a CBS special about the spike in black lung and about his years in the mines and the toll that it took on he and his family. "My lungs are turning to rock," he said.

He said when he was first diagnosed with advanced black lung, "it was a complete shock to me. Everyone you see who has it is old."

As the disease progressed, he became tired sooner and struggled to take walks with his 5-year-old daughter, Dixie. "She'll be running uphill and say, 'Hurry up, Dad.' I don't think she quite understands."

At times, he says, "it feels like someone is standing on my chest."

He spoke at a black lung conference last month in West Virginia, where he told his story to hundreds of people. The public often hears about the disease from older miners, but "I feel like I can make more of a difference because of my age," he said.

"I don't know what my future holds," he said. "But if I can keep some other little girl's daddy alive so that they can experience life events like being there at her high school graduation, then it's worth it."

Deputy Managing Editor for Investigations Michael Sallah contributed to this report.

Reporting and Writing By MICHAEL KORSH OF THE PITTSBURGH POST-GAZETTE AND PHILLIP POWELL AND YIQING WANG OF THE MEDILL INVESTIGATIVE LAB; read the full story here. https://www.post-gazette.com/news/health/2024/07/21/black-lung-coal-mines-silica-dust/stories/202407170071

Deep fear in coal country: DOGE cuts put region's miners and families on edge

Nurse practitioner Shelly Pack checks Randall Dickerson, 49, breathing inside Bluestone Health Association’s Black Lung Clinic on Wednesday, March 26, 2025, in Princeton, W.Va

For federal safety inspectors, the urgent call to their sprawling mining office near Pittsburgh was bleak: Man crushed in the rubble of an aging mine in the heart of coal country.

Agents from the Mount Pleasant office arrived shortly after the body of Joseph Guzzo Jr. was pulled from under the massive chunk of earth that collapsed in the underground tunnel four years ago.

Then, months after launching an investigation that found the operator failed to provide critical protections, it happened again.

Another worker in a mine just an hour away suffered catastrophic injuries after a large rock broke from a wall and slammed him against a machine.

Year after year, the local office of the Mine Safety and Health Administration — the most active mine safety center in the nation — launched inquiries into deaths and devastating injuries in some of the largest underground caverns in the country.

Now, the facility long entrusted with the protection of workers is among 34 centers in the United States that are expected to be shuttered in sweeping cuts to the federal agency that have not been felt in years.

In an ongoing effort to slash spending, the Department of Government Efficiency has targeted the mining agency in a move that surprised local inspectors and raised questions about the future of regulation in one of the country’s most dangerous jobs.

“Without the federal inspections, coal operations will just run rampant,” said Tony Oppegard, a former Kentucky mine safety prosecutor and MSHA legal adviser. “There won’t be any accountability.”

It’s not clear if the agents at the Mount Pleasant office will be transferred or lose their jobs, but the cancelling of the leases comes as the number of injured workers has been increasing in some of the most active mines in the U.S., the Post-Gazette has found.

At the Marshall County Mine in West Virginia, one of the largest producers of coal in North America, the injuries rose by more than 50 percent from a decade ago, records show.

Randall Dickerson, 49, has his lungs x-ray to document his black lung inside the Bluestone Health Association’s Black Lung Clinic on Wednesday, March 26, 2025, in Princeton, W.Va

At the Buchanan Mine in Virginia, the numbers of miners hurt on the job increased ninefold — from three injuries to at least 27 during the same period.

The toll on miners continues to grow as operators look for ways to dig deeper into the seams and to churn out more coal in an industry that has been shrinking for years and struggling to stay competitive.

“The deeper you go — 80 feet, 120 feet — the higher the probability of roof falls,” said Mr. Oppegard.

Raised alarms

Though the number of workers dying in coal mines has dropped dramatically from decades ago when fatalities were in the hundreds each year, miners still face risks.

In the past decade, more than 100 have perished in accidents — including explosions and collapsing tunnels — with one in every seven cases investigated by the Mount Pleasant office.

DOGE did not respond to emailed questions from the Post-Gazette about the future of the safety center, which has been operating in the same building in Westmoreland County for more than 15 years, records show.

The Post-Gazette reached a supervisor at the center who said federal agents have not provided any details about plans for the facility. "I don't know anything more," said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I’m reading what you’re reading.”

Amanda Lawson, longtime benefits counselor at the Bluestone Health Association in Princeton, W.Va., spends her days meeting with miners in need of black lung benefits – a job that consumes her. “This is their whole life,” she said.

Three other offices in Pennsylvania are also on the list of lease cancellations: the Warrendale district center, Waynesburg in Greene County, and Frackville in Schuylkill County. The savings in terminating the leases: $2.5 million.

The move by the new agency is the latest in a series of actions by federal officials that have raised alarms among safety advocates, who have long pushed for greater safeguards in mining.

After years of medical experts warning about a new form of black lung disease caused by an insidious toxin — silica dust — federal regulators created a rule that would force coal operators to drastically reduce exposure levels underground.

The protection, which cuts in half the amount of silica allowed in the air, is set to take effect next month, but is now under legal challenges by trade groups and allies in Congress who are threatening to roll it back under the new administration.

One of the groups that’s fighting the rule was once led by Wayne Palmer, who was recently nominated to become the next leader of MSHA.

The safeguards, which could cost mine owners millions of dollars a year to implement, are aimed at slowing the spread of a disease that’s now impacting the new generation of miners.

Nowhere has the sickness ravaged miners more than in Appalachia, where the workers are eight times more likely to die from the disease than anyone else in the country, according to a federal study two years ago.

Amanda Lawson comforts her father, Danny Johnson, 71, who has been battling black lung disease for years. Like so many former coal miners afflicted with the illness, he uses a nebulizer and inhaler to help him breathe.

With particles embedded deep in the lungs, the illness eventually creates scarring and a thickening of the inner walls that make it much more difficult to breathe.

“It’s a struggle,” said Jimmy Phillips, a retired West Virginia miner who was diagnosed with black lung a decade ago. “It feels like someone put an elephant on your chest after you go a little ways.”

Year after year, he and others suffering from the disease travel to the Bluestone Health Association clinic in Princeton, W.Va. — some strapped to oxygen tanks or carrying inhalers.

There, they get breathing treatments, medication and other care for an illness that has no cure.

Though the clinic is funded partially through federal grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration, safety advocates say they’re concerned the money could be reduced or end under the new administration.

“I could be out of a job by June,” said a health staffer who works at another lung clinic across the state.

‘Keeping men alive’

Debbie Johnson, a nurse and program director at the Bluestone clinic, said too many people with black lung depend on benefits and the support of the centers for the money to stop.

“It’s about keeping these men alive and making sure they have a life worth living,” said Ms. Johnson. “They can’t do without it.”

Her 71-year-old husband, Danny, a retired miner who has been diagnosed with the illness, relies on the facility for his own treatments and periodic exams.

The disease has so ravaged his lungs that, on most days, he keeps an inhaler close by, using it “every day. Three, four, five times a day. You aren’t supposed to use it that much, but I do,” he said.

Danny Johnson, 71, shows some of the medication he takes as he struggles with black lung disease.

Another visitor, Randall Dickerson, 49, is like so many others: The simple tasks of life are often insurmountable. "For me to walk 100 feet — it's tough," said the married father of three.

"I wake up in the morning, I’m coughing my brains out. I have to use an inhaler and an oxygen machine, and I’m not even 50. That should never happen at my age.”

When the illness is caused by silica — fine crystals that are more dangerous than coal dust — the chances of survival grow even more grim, experts say.

“It’s like pieces of glass eating into your lungs,” said Amanda Lawson, a Bluestone benefits counselor who works with her mother, Ms. Johnson, at the center.

In an email, HRSA said the current funding for lung clinics ends in June, but the agency recently accepted applications for the next cycle, which is supposed to provide a total of $12 million.

As the clinics take in a growing number of patients, the burden of preventing more people from getting the disease continues to fall on the safety inspectors.

Without enforcement of the silica threshold, miners will continue to be exposed to toxic levels of the dust that go far beyond the bounds of safety, say medical experts.

In the mines of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, it’s a particularly acute danger.

Over the past decade, more than half the mines in the U.S. that exceeded the threshold were in the two states, a Post-Gazette analysis shows.

In Pennsylvania's Clearfield County, one dust sample alone from the Hoover Job Mine showed the highest levels of silica of any mine in the country — more than 17 times the threshold.

The growing number of black lung cases is yet another reason that the ranks of federal inspectors should be bolstered rather than cut back, say safety advocates.

“MSHA is really on the front lines,” said Dante diTrapano, an attorney in West Virginia who represents the underground workers. “If there are further cuts, this could impact their ability to do their job.”

he Marshall County Mine in West Virginia, which is surrounded by industrial sites including a coal processing plant and coal-fired power station, is one of the largest producers of coal in North America.

Critical check

The agency has faced criticism in the past for missing inspections and, at times, not imposing severe punishment on some mine owners who ignored the laws.

But MSHA has also served as a critical check on dangerous practices that defined the industry generations ago.

Wendle Hopkins spent weeks in a hospital bed in 1974 — his battered body covered with burns — after an explosion sent him hurtling through a tunnel in a mine in McDowell County, W.Va.

He said he was never interviewed by investigators, nor was he aware of any disciplinary action against the company. “It was like nothing happened,” said Mr. Hopkins, now 69.

While federal safety standards have increased, miners continue to face risks that few other workers confront.

One in every five who died on the job in the last decade were killed by collapsing walls and ceilings — in many cases after operators failed to follow their own safety plans, records show.

In the death of 32-year-old Joseph Guzzo four years ago, the operator of the Kocjancic Mine in Jefferson County had pushed deep into the cavern, beyond where workers had sunk bolts that were supposed to be used to keep the roof from caving in.

Debbie Johnson, a nurse and program director at a West Virginia health clinic that treats patients with black lung, prays before dinner with her husband, Danny, a retired miner who is diagnosed with the illness, and her daughter, Amanda Lawson, a benefits counselor at the clinic.

A 12-foot-by-nine-foot slab broke free as Guzzo was running the mining machine, falling on top of him.

The Mount Pleasant office of MSHA imposed several citations on Rosebud Mining Co. in what became the first death in coal mines that year.

The veteran miner left behind a 7-year-old son, Joey.

The events that led to the accident were “egregious,” and the death “could have been avoided,” said Mr. Oppegard, the former Kentucky mine prosecutor. “They cut twice as deep as they were supposed to.”

He said such breakdowns are part of a larger pattern of coal companies taking risks that have long persisted in the industry.

Edgel Dudleson, 67, who toiled underground for years in West Virginia, said in most cases, workers would rarely speak up about the hazards because “they were afraid of losing their jobs.”

But with inspectors at the scene, operators were forced to address problems that workers faced everyday, he said.

Even with the inspectors, dangerous conditions can be overlooked and violations are not always imposed on mine owners who break the law, Mr. Oppegard said.

But without the regulator, “my fear is it’s going to lead to more unsafe mines,” he said. “They used to say the best days for the coal miner are the days when the inspector shows up.”

Anavi Prakash, Tianyi Wang, Jessie Nguyen and Victoria Malis of Northwestern University’s Medill Investigative Lab in Washington, D.C., contributed to this report.